Philadelphia Magazine

Don Steinberg 1/25/2020

Like any smart CEO, David Field knows that you lead with the good news and try to hum a happy tune over the bad, especially when you’re talking to Wall Street. So when he got on the speakerphone on August 7, 2019, for his company’s second-quarter earnings call, he held back the financial results for a minute and opened with some promising news: Entercom, the quiet media giant based in Philadelphia, the second largest radio broadcaster in America, had just acquired two companies that produce podcasts.

Podcasts are really growing. The traditional radio business that built Entercom really isn’t. So anything that suggests being around to participate in the future of media is encouraging.

“We are poised to become one of the three largest podcast enterprises in the United States,” said Field, Entercom’s CEO. He also said Entercom had launched the Radio.com digital sports network, letting listeners, via a mobile app or website, tune into the dozens of sports radio stations Entercom owns around the country, including WIP in Philly. The network could give advertisers an unrivaled way to reach men who like to hear other men talk about sports.

Then Field unpacked the financials to provide the latest scorecard on Entercom’s progress in making a much bigger acquisition work — the largest and most existential deal in its history.

In 2017, Field bet the company, which his father started in Center City in 1968 and moved to Bala Cynwyd in the early ’70s, on an ambitious takeover of the radio stations CBS was divesting. The CBS Radio deal nearly doubled the number of stations Entercom owned, from 125 to 235. By revenue, CBS Radio was about three times the size of Entercom. The transaction took Entercom, for the first time, into big markets like New York, Chicago and Philadelphia. (It now owns KYW, WIP, WOGL, WPHT, 96.5 TDY, and, through a secondary transaction, B101). Entercom became America’s largest owner of all-news and sports-talk stations.

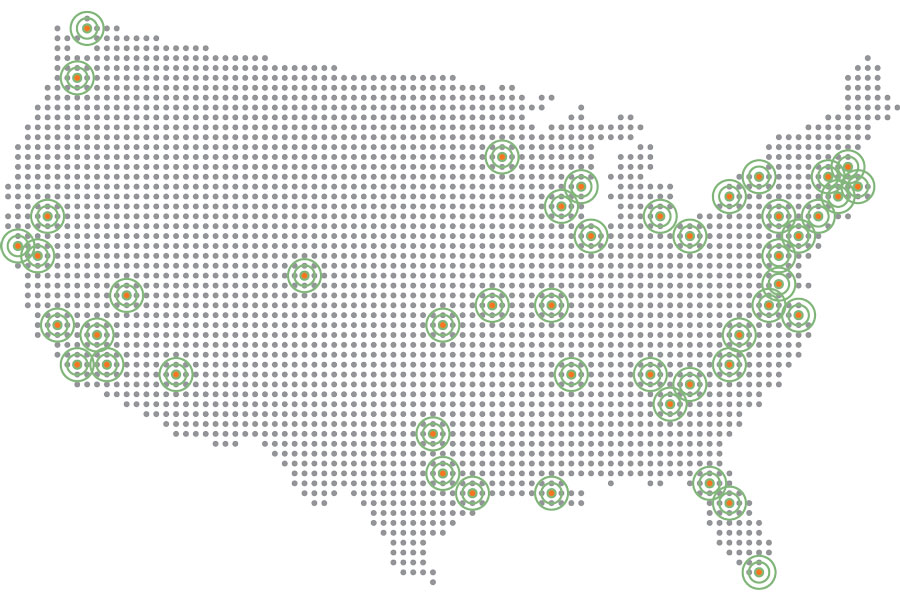

The Entercom Empire: After acquiring CBS Radio, Entercom became America’s second largest radio broadcaster. It currently has 235 stations in 46 markets across the country, including KYW, WIP, WOGL, WPHT, 96.5 TDY and B101 in Philly.

The company took a gigantic bite of debt in doing the deal, but the media business is eat or be eaten. Field saw the CBS stations as complementary to those Entercom already owned, creating a network with enough reach to compete with anybody for national advertisers. He suggested that the CBS stations were undermanaged. There was upside to exploit, as well as cost-saving opportunity in the combination of the two companies. Plus: CBS had Radio.com, the web address and mobile app, which, if tuned up properly, could help Entercom gain from the future of digital audio flowing through phones, AirPods, vehicles, and smart speakers like Alexa that everyone keeps buying.

Even traditional broadcast radio still had legs, Field believed, because it was undervalued. The public spends about 16 percent of its daily media time with radio, but radio gets only about seven percent of media ad spending dollars, he liked to point out. If ad buyers could be persuaded to appreciate the value of radio commercials even a little more, Entercom could grab a bigger slice of a $200 billion pie.

Field promised long-term but not instant success. He needed to cut costs and grow at the same time. He hoped investors, most of them former CBS shareholders who swapped for Entercom shares, would trust the process.

In general, they haven’t. Entercom’s share price fell 25 percent in 2017, landing it among the worst-performing tech stocks of the year — a year in which the Dow Jones index was up 25 percent. Entercom had opened at $16.55 on the day the Wall Street Journal reported the agreement to buy CBS Radio, but the evening before, when Field was giving his August report, the stock was slumming at $5.25. Wall Street wasn’t buying Entercom’s future.

On the speakerphone, Field announced positive second-quarter numbers: Entercom’s revenues were up 2.3 percent. “Audio is in the midst of an emerging renaissance, and we are well positioned to participate in that opportunity,” he said. “Frankly, it is remarkable that in the light of all this, our stock continues to trade where it does … we see our stock valuation as a complete disconnect with where we see the business.”

Alas, stock analysts expected Entercom’s quarterly numbers to be higher. Following the call, Entercom stock dropped 36 percent more, to $3.36, a new low. Observers cringed. Big institutional investors don’t like stocks below $5.

ENTERCOM HAD ALREADY been through a challenging couple of years. As in any corporate merger, the integration of the CBS stations and employees had its pain. Policies were changed. WIP’s signature event, raunchy and ribald Wing Bowl, was killed. There were staff cuts in cities where Entercom and CBS overlapped.

“Entercom was the fish that swallowed the whale,” one former company manager told me. “They’re a medium-market operator, and they thought that they could keep doing things the same way. It became immediately apparent to everybody inside that they were not equipped for that.” (Author’s note: I began work on this story in 2017. Entercom initially participated, then decided to hold off, until now. The delay gave me an inordinate amount of time to speak with former employees now outside of CBS/Entercom. Many don’t want to be identified, so I quote selected comments without names attached, understanding that bitter honesty can be flavored by sour grapes and allowing Entercom a chance to respond.)

Many managers who left the company repeated the sentiment that Entercom brought an assertive “top-down” management style that undermined authority at local stations over decisions like talent contracts, sports play-by-play licenses, even on-air promotions.

“They ran Entercom like a much smaller company, like a family business,” one person told me. “You can do that when you’re in markets like Buffalo and Rochester, but not in New York, Chicago. I think they didn’t anticipate what they didn’t know.”

Robert Feder, a longtime reporter on Chicago media who has an industry blog, put it bluntly: “I’d be hard-pressed to think of a single way in which the Chicago group is better off under Entercom than it was under CBS Radio. Many, many jobs have been cut, others have been combined, and much of the group’s local programming and operational autonomy has been lost. A day doesn’t go by that I don’t hear complaints from employees about corporate meddling and mindless cost-cutting. In short, it’s been pretty much a disaster from day one.”

To add injury to insult, Entercom was hit by a cyberattack in September, which it acknowledged cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost revenue.

But David Field isn’t deterred. He has a plan, a process. When I speak to him in November, inside Entercom’s new Center City headquarters, he dismisses those top-down, small-town gripes.

“I don’t agree with that,” he says. “I mean, we have been in San Francisco. We’ve been in Boston, we’ve been in Los Angeles. Everybody’s entitled to their opinion. But all of our program decisions are made locally. Whether it’s selecting music, coaching their personalities, that’s all done locally. Sales decisions are all done locally. Which, of course, doesn’t mean that there aren’t sort of strategic initiatives from corporate. But I’d say it’s a very collaborative organization, very entrepreneurial at the local level.”

Traditional AM/FM radio is at a crossroads. America’s two other largest radio companies, IHeartMedia and Cumulus Media, have gone through recent bankruptcies, suffocated by debt. Most radio listeners now listen only in the car, where there’s growing competition for ear time from satellite radio and Bluetooth-connected phones. Young people are discovering music on Spotify and Pandora, YouTube, Twitter, TikTok and Tinder. Research from MusicWatch found that among 13-to-24-year-olds, music listening hours are four times higher on streaming platforms than on AM/FM radio.

But David Field thinks there’s a way to save radio. Humanity is consuming more audio content than ever. We’re evolving into a species with little speakers jammed in our ears. Imagine a company poised to deliver all that sound. Sure, Spotify, Pandora, blah, blah. But algorithms can’t replace the familiar voice who finds you in your car on a bad night and makes you laugh and cues up “Livin’ on a Prayer” to drive you home.

When I show Field a chart depicting radio industry revenues as flat for the past five years, he talks about smart speakers and podcasting and voice-activated searches. “We’re focused forward.”

Even the pay services that steal attention — Netflix, Amazon Prime, satellite radio — bring something of a benefit, because advertisers can’t spend their budgets on services that don’t run ads. “As others become less advertising-supported, doesn’t that create opportunity for us?” Field asks.

When I show Field a chart depicting radio industry revenues as flat for the past five years, he talks about smart speakers and podcasting and voice-activated searches. “I think that is the rearview mirror,” he says about the chart. “We’re focused forward.”

You had your time, you had the power

You’ve yet to have your finest hour …

Radio, what’s new?

Radio, someone still loves you— Queen (1984)

ENTERCOM STARTED in 1968, but one thing David Field insistently doesn’t want to talk much about is its past. In a city with such a rich media history, it seems like a lost opportunity to join the folklore. Philadelphia-based Atwater Kent and Philco were among America’s biggest radio manufacturers. The department stores along Market Street built early radio stations to attract shoppers. Gimbels started WIP in 1922. WCAU was a CBS Radio flagship station in 1927 and helped finance television’s early years. Hy Lit and Jerry Blavat pioneered rock-and-roll radio in Philly. MMR and YSP and Q102 led the FM explosion. Terry Gross took Fresh Air national from WHYY. And now one of the premier radio broadcasters in America is right on Market Street.

I understand David Field’s reluctance to relive the thrilling days of yesteryear. Commercial radio turns 100 years old in 2020, but so-called “legacy media” operators are desperate to cut ties with the golden days and make futuristic versions of themselves seem plausible. The radio format with the greatest loss of stations in recent years is “oldies.” If you’re trying to appeal to the next generation, it’s a good idea not to put oldness right there in your product name, boomer.

I also got the sense that Field, who’s 57, isn’t interested in being depicted as the privileged heir to a business that his dad, Joseph Field, started. Maybe he saw my Philadelphia magazine article, many years ago, about Comcast CEO Brian Roberts and his company-founding father Ralph Roberts, where I kind of did exactly that.